Larry Gross, president and founder, Gross Transportation Consulting, and JOC analyst | May 19, 2021 9:26AM EDT

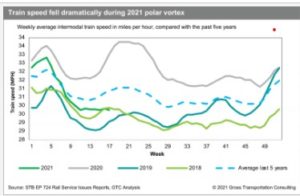

Intermodal train speeds in 2021 have been well below the average of the past five years and far below the same time in 2020.

The US intermodal network is hardly unique in being stretched beyond its limits at this time. Every aspect of the supply chain, it seems, is suffering the same fate. But the railroad industry just underwent a transformation that was supposed to usher in a new era of dependability and resiliency: precision scheduled railroading (PSR). Unfortunately, the sector’s performance thus far this year seems to show — with certain exceptions — that what worked in theory seems to be lacking in practice.

While good service reliability data are not available for intermodal, the US Surface Transportation Board (STB) has required over the past three years or so that the big railroads operating in the United States report certain service statistics on a weekly basis. While these statistics are of limited utility, there are a few concerning intermodal that can provide at least some indication of the performance of the intermodal network. What are these numbers telling us?

The three main statistics that have bearing on intermodal are average intermodal train speed, intermodal trains being held idle for some reason (waiting for crews, waiting for power, or “other”), and the number of intermodal cars that have not moved in a period of 48 hours or more. These numbers provide an indication of the fluidity of the rail network, at least in terms of train movements. The glaring omission is that they tell us nothing about the intermodal terminal operations or how well equipment is navigating the modal transition from rail to highway and vice versa. While the STB does collect data on yard dwell from the railroads, this represents railcars moving through classification switch yards and not intermodal terminals.

Nevertheless, in a dark room, even a small candle has value. Given the general lack of publicly available data, we can work with these figures.

What the numbers are telling us is that the network is struggling across all three dimensions. Train speeds thus far in 2021 have been well below the average of the past five years and far below the same time in 2020, when trains were speeding across a wide-open network with little other traffic to impede their passage. Of more concern is that there seems to be little sign of improvement. Typically speeds tend to ramp up this time of year. But in 2021, speeds fell dramatically during the polar vortex and have not improved since.

Looking at the average number of intermodal trains being held and how this figure compares to the past three years, the time period for which the STB has required this reporting, the story is also unfavorable. During the polar vortex, the number of intermodal trains holding for crews, power, or other reasons skyrocketed to the highest levels yet seen. They have since receded but recently the number has been rising again. The 35.3 average trains holding in week 17 was the highest level seen yet for that week.

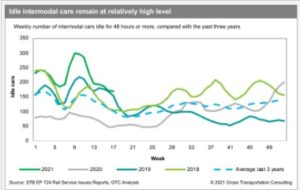

The number of loaded intermodal cars that have not moved over a period of 48 hours was also badly affected by storm disruptions and remains at a relatively high level. It should be noted that these cars represent well less than 1 percent of the total intermodal cars on the system, but it is also a legitimate question as to why any significant number of loaded cars should be stationary for such a long period.

The railroads will justifiably point out that the polar vortex was a severe event, and that the relentless surge of intermodal traffic has been tough to keep up with. But it is equally fair to point out that winter comes every year, and this one was relatively mild overall, albeit with the exception of the singular polar vortex event. Volume is strong but the system was also operating at similar levels for most of the second half of 2018. Why has this time around proved so difficult?

One potential reason can also be applied to other modes, in fact across the supply chain. A big piece of the PSR revolution was the “right-sizing” of operations to meet demand. Assets are utilized more intensively and productively, yielding significant cost savings. But if the network is close to fully utilized under normal circumstances, yielding peak efficiency, the results seem to imply that it then has limited resiliency and capacity to deal with the unexpected, be it a disruption or unexpected volume.

But to be fair, the situation is not problematic across the board. Some railroads are performing better than others. CSX is generally still running better than it previously did in the pre-PSR days despite these problems. CSX began the PSR transformation earlier than the other railroads so perhaps they too will improve as time goes on and they continue to optimize their systems. But it is also possible that in their cost-cutting zeal, the railroads shed more than just fat, but some muscle and bone as well. Perhaps some of the terminals that were closed would come in handy right now. 10,000-foot-long trains are highly efficient, but perhaps more difficult to deal with in less-than-optimal conditions.

The larger lesson for shippers is that all modes are seeking to undertake these kind of capacity adjustments. Surge capacity will no longer be free for the taking, but rather increasingly expensive, if it is available at all. Those who maintain close working relationships with carriers and more awareness of the mutual challenges and needs will be in a position to better navigate the next inevitable challenge.

Contact Larry Gross at lgross@intermodalindepth.com.