As ship queues off the US West Coast decline, the focus is shifting once again toward the railroads, who are being identified as the next big “bottleneck.” But that’s only part of the story. The root cause of the problem are the ocean carriers, who continue to make decisions based purely on what is best for them at a particular moment with the expectation that the inland transport system will “just deal with it.” This is substantially evident in what has taken place lately in the inland point intermodal (IPI) sector.

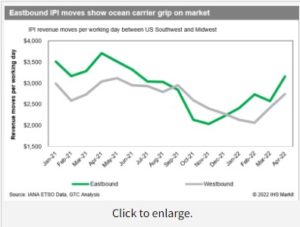

This chart shows the IPI revenue moves per working day by month moving between the Southwest region and the Midwest region as defined by the Intermodal Association of North America’s ETSO database. The ocean carriers substantially control this market, selling service from origin to inland point to the beneficial cargo owner (BCO) and purchasing transport for their boxes from the railroads via long-term volume contracts. Some of these containers flow back as export loads, but most move back as revenue empties, again, as directed by the ocean carriers. Either way they show up in the data, just so long as the railroad gains any revenue at all from their movement.

Eastbound volume peaked in April 2021 with about 3,700 boxes (not TEU) moving per day. But there were only 3,000 per day going back west. In other words, there was a 700-container-per-day deficit that needed to be covered. That is two or three completely empty stack trains of railcars moving west each day in order to support the eastbound surge. The chart shows that this large imbalance was in place every month from January through April 2021 before the gap began to shrink, mainly because the number of eastbound containers fell, and not because the westbound flow increased.

Why did eastbound numbers drop?

There has been a lot of finger pointing as to why the eastbound numbers dropped. The ocean carriers would say it was the choice of the BCO, reacting to inland congestion. But there is ample contrary testimony indicating that the ocean carriers “encouraged” alternatives to IPI through not offering inland service to BCOs or quoting sky-high rates. Why? Because they were short of equipment and wanted to slingshot the boxes back across the Pacific ASAP in order to be in position to collect the next very-high-margin eastbound load. This was most evident in October when the eastbound IPI volume dropped by an incredible 25 percent in a single month.

Meanwhile, the westbound flow of empties continued, now exceeding the eastbound volume per day. Is it any wonder that the ports and surrounding region got clogged with empties? In October, there were over 460 excess containers flowing into the region each day via rail that needed to be handled, stored, and eventually, loaded onto a ship.

After November, however, the ocean carriers turned the eastbound IPI switch back on. The international shortage of containers had eased somewhat and there now were enough containers in Asia to cover the outbound demand, so they no longer felt they needed to conserve equipment by keeping it corralled near the ports. Between November of last year and April 2022, IPI volume moving eastbound each day increased 55 percent. Once again, there is a huge imbalance between inbound and outbound moves, as big as 700 containers per day in February.

All concerned need to understand that there is a limit to how much of this push-and-pull volatility these massive inland systems can withstand. Similar to a 24,000 TEU ship, with all the moving parts, they can only change course so fast. The system would work a lot better if the various parties, most particularly the ocean carriers, worked in a more collaborative fashion. Could the railroads have handled the situation better? Sure. But to point the finger of blame solely in their direction is missing a root cause of the problem.

Soon, however, this will all be ancient history. The historic trans-Pacific bonanza is coming to a close, and soon the ocean carriers will be awash in capacity, with more coming on-stream. The flow through ports will become more fluid and the volumes less volatile and irregular. The question is if and how and the system will be changed in the coming months and years so as to help keep the problems seen during the most recent challenges from repeating the next time the inevitable crisis rolls around.