In response to the current service issues on the US freight rail system, the Surface Transportation Board (STB) has mandated that the Class I railroads report an additional raft of metrics on a weekly basis, including — for the first time — on-time arrival data for intermodal trains.

The data is of somewhat limited utility because it measures the percentage of trains arriving at their destination terminal within 24 hours of schedule. This broad measure is perhaps more appropriate for a merchandise train of conventional railcars than it is for the more service-sensitive intermodal segment. This is particularly true of the domestic intermodal sector, where intermodal is competing with trucks, which measure “on-time” performance in minutes, not one-day increments.

It also tends to skew results in favor of eastern railroads, not necessarily because their performance is all that much better, but rather because the lengths of haul are shorter and, therefore, trains leaving the East Coast are less likely to lose a full day during transit.

And despite the interconnectedness of the North American intermodal network, the Class I railroads based in Canada only report on the US portions of their operations, and Kansas City Southern does not report on what’s happening in Mexico. The data also is not offered in a particularly user-friendly format, with each railroad reporting on a separate spreadsheet every week.

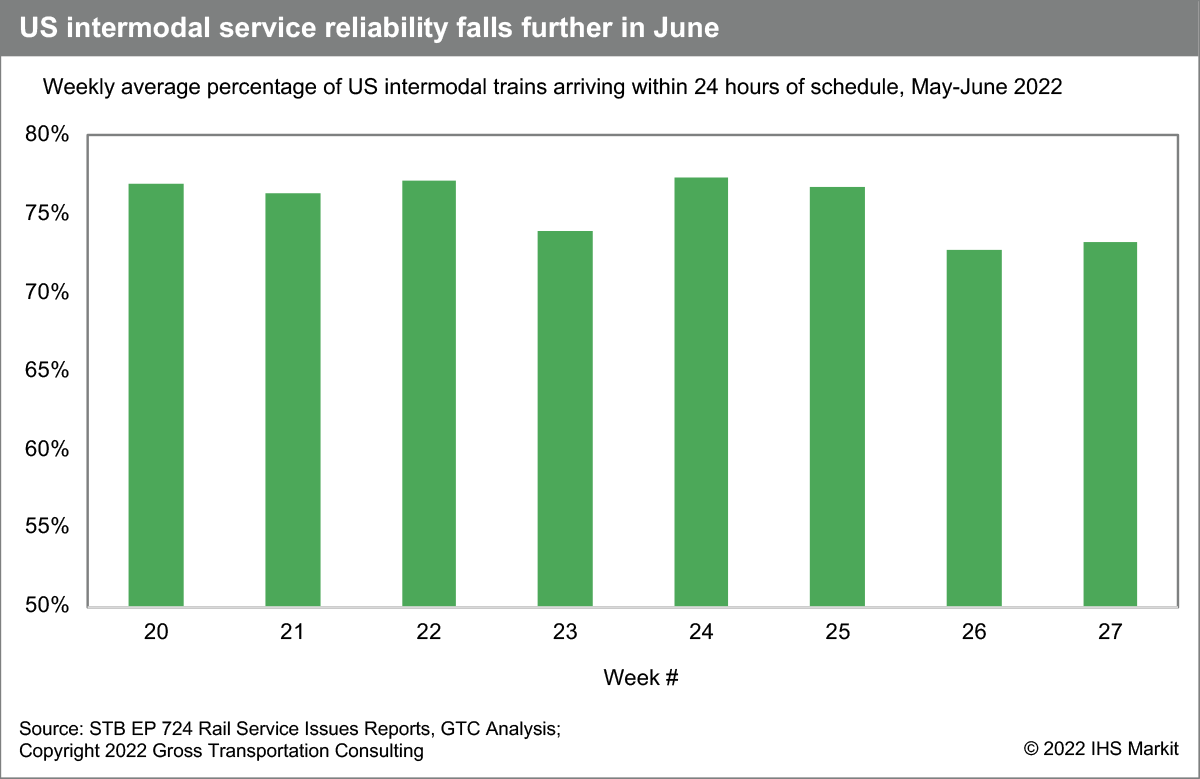

But in a completely dark room, even a small candle can make a big difference. More important than the absolute number of trains arriving on time is whether the trend is heading up or down, and thus far, the data is not very encouraging.

On a composite basis, approximately one out of every four intermodal trains operating in the United States arrived at its destination more than 24 hours behind schedule in the eight weeks ended June 29. This average is based on each railroad’s on-time percentage weighted by the number of intermodal cars on the railroad. Most alarming, on-time performance was just 73 percent, the lowest yet recorded, in the last two weeks.

Looking at the individual railroads, western Class Is BNSF Railway and Union Pacific Railroad (UP) show considerably lower on-time performance than eastern lines CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern Railway (NS). For the week of June 29, 67 percent of UP intermodal trains arrived on schedule, slightly better than BNSF’s performance (57 percent), but still well below that of CSX (96 percent) and NS (89 percent).

The railroads, which cite personnel shortages as the biggest impediment to improving service, are frantically trying to recruit and train new conductors to help get their staffing up to the required levels. But training for safe operation on the railroad is a lengthy process and, as such, relief still lies some distance in the future. That today’s workers seem less inclined to accept the lifestyle trade-offs required to work for a railroad, even if the wages are competitive, poses additional problems in recruitment.

Intermodal volumes handled by the US Class I railroads dropped 6.2 percent year over year in the first half of 2022, according to data from the Association of American Railroads (AAR). The last four weeks of the half weren’t much better, with volumes coming in 4.6 percent lower than in the same 2021 period.

The railroads are talking about intermodal as a growth story, but the reality says something else. Until they can better control the quality of their service offering, it may be unrealistic to expect a turnaround in intermodal volumes.