A coast-to-coast national intermodal network, formed by pairing an eastern carrier and a western carrier, would put intermodal on a more even footing with truckload carriers that don’t face interregional obstacles, writes analyst Larry Gross.

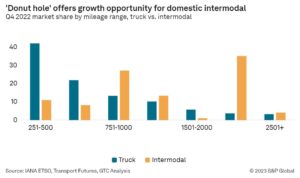

Take the distribution of long-haul truck and intermodal by mileage range for the fourth quarter of 2022. Of all the dry van and reefer truckloads moving more than 250 miles from door to door, some 42 percent were concentrated in the 251- to 500-mile range. In contrast, only 11 percent of all intermodal moves took place within those lengths of haul.

The truckload data follow a logical pattern. Volume was concentrated at the shorter lengths of haul. The longer the haul, the less volume was moving. But intermodal had a completely different and very unusual volume distribution. The two biggest mileage ranges are 2,001 to 2,500 miles, which accounted for more than 35 percent of all moves, and 751 to 1,000 miles, which represented another 27 percent. In total, almost two-thirds of all intermodal activity occurred in these two mileage ranges. Meanwhile, a relatively paltry 14 percent moved in the intermediate 1,001- to 2,000-mile range.

This “donut hole,” also sometimes referred to as the “watershed problem,” represents a major growth opportunity for domestic intermodal. It exists because most of the hauls in this range require interchange between two carriers. Tapping it often requires the railroads to steel-wheel interchange a myriad of small blocks of traffic. Such complexity is anathema to railroad operating departments, particularly in the era of precision scheduled railroading.

The “solution” then becomes a rubber-tire crosstown interchange. This eliminates the operational complexity. Unfortunately, it also converts what should be a solid intermodal opportunity into two standalone short-haul moves with a high-cost dray move inserted in the middle. More often than not, this alone blows up the competitive economics. Moreover, very often the length of haul on one side or the other of the interchange point is very short — too short for the railroad involved to bother with it. So, the required short-haul intermodal move to the interchange point becomes a long-haul dray move. By the time one reaches the terminal where the intermodal second stage begins, it’s no longer worthwhile to put it on the rail. It becomes so much simpler and probably more economic to just keep it on the highway for the rest of the way.

Coast-to-coast intermodal network?

Interestingly, the same calculus applies to the ultra-long-haul market of over 2,500 miles. These hauls also almost always require two railroads to be involved. The economics of intermodal indicate that it should shine in this market, but it actually does no better than truck.

One obvious solution to the problem is merging the railroads. If one railroad controls both legs of the haul, then the interchange problem is largely eliminated, and the interchange locale simply becomes another city along the way. But a coast-to-coast railroad merger simply isn’t in the cards.

The question is whether an intermediate solution can be devised to address this problem. It would be a coast-to-coast national intermodal network, formed by pairing up an eastern carrier and a western carrier. In one sense, this would diminish competition because the number of routing options would decline. But it would put intermodal on a more even footing with the truckload carriers, which don’t face these kinds of interregional obstacles.

This might be a pipedream, but even small steps to address these markets could result in much-needed volume growth.

Contact Larry Gross at lgross@intermodalindepth.com.