Nothing lasts forever, it seems. A well-crafted “better mousetrap” turns in great results, perhaps for an extended period. But eventually conditions change, and the finely tuned mechanism that had generated stellar results begins to creak and sputter.

Such is seemingly the case in the cross-border market linking the ports of Western Canada with the US Midwest. For many years, these cross-border services for intact ISO container moves were an outperformer as compared with the rest of the intermodal network. But that is no longer the case.

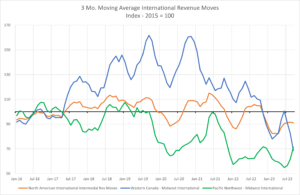

The chart below looks at the quantity of ISO containers between Western Canada and the US each month and compares this data with the corresponding volumes moving between the US Pacific Northwest and the Midwest, as well as the total number of North American intact ISO container moves. For each, the average monthly moves in the year 2015 are set at an index level of 100. The chart displays the performance based on the three-month moving average in subsequent years up through September of this year.

Sources: IANA ETSO, GTC Analysis

The chart reveals that a remarkable sea-change has taken place recently. Beginning in 2017, the Canadian services began to significantly out-perform both the competitive all-US option via the Pacific Northwest (PNW), but also international intermodal as a whole. Their index values reached as high as the 160s in 2019 and 2020, implying growth of 60% from 2015. Meanwhile, volumes moving between the PNW and the Midwest didn’t grow much at all through 2019 and then suffered significantly thereafter. Overall international intermodal volume puttered along during most of the ensuing years, sometimes showing 10% gains versus 2015 but unable to sustain that level.

All the services contained in the chart are currently in negative territory compared with 2015. In other words, volume has been running lower of late than it was some eight years ago. But the fall from grace of the Canadian option has been particularly notable.

IPI volumes down more than imports

The drop in inland point intermodal (IPI) volumes has been greater than the drop in imports. For the 2023 third quarter, IPI movements between Western Canada and the Midwest were down 38% versus prior year, while import TEUs arriving in Western Canada were down “only” 27%.

A more detailed look at import TEUs suggests that more of the problem is centered in Prince Rupert than in Vancouver. Import TEUs landing in Western Canada were down 68,000 TEUs in Q3 2023 versus the same period in 2022. Prince Rupert accounted for more than half of the loss, even though its volume was much lower than Vancouver. Vancouver import TEUs were down, but only by about 19%, while Rupert lost about 57% of the Q3 2022 imports.

Perhaps one reason for Rupert’s woes is its heavy imbalance. For the months June through August 2023, the ports of the US and Western Canada collectively received about 2.1 loaded inbound TEUs for every loaded outbound. The Western Canadian ports received 2.6 loaded inbound per outbound load, so their imbalance was worse. But drilling down, Vancouver’s imbalance was 2.45:1.0 while Prince Rupert’s was 3.4:1.0. There’s not much new there, as Rupert has always been a heavily inbound port. But perhaps what has changed is the tolerance level of ocean carriers. Perhaps they are routing cargo toward ports where they have a better chance of scoring a backhaul.

This thesis may help explain the thinking behind the recently announced transloading facility for Prince Rupert. Unlike the transload operations in Southern California, this project is not about transloading cargo from inbound ISO containers into 53-foot domestic boxes. Rather, it is about transloading neo-bulk export cargo such as grain and forest products from railcars into empty outbound ISO boxes.

While it won’t do anything to affect the rail imbalance in containers to and from Prince Rupert, it could do a lot to address the imbalance on the ocean side. This should improve the economics of Prince Rupert and could prove useful in attracting more import volume as well.

Contact Larry Gross at lgross@intermodalindepth.com.