It’s going to be a rough one. Like a giant ship that has lost all power, the U.S. economy is slowing rapidly and with it, freight demand. Supply chain participants should be planning for the potential for a crisis that will meet or exceed the downturn seen in the Great Recession. Yet, using history as our guide, even in a situation as bad as the COIVD-19 lockdown, there may be opportunity for domestic intermodal, if the industry is prepared to grasp it. But it won’t happen as long as the industry maintains its laser focus on Operating Ratio.

On March 28, as the COVID-19 crisis gathered steam, I found myself reading an excellent piece in the New York Times titled: “Alone on the Road, A Trucker’s Long Haul as America Fights the Virus”. It described the difficulties an owner-operator was encountering navigating through the strange new pandemic world, traveling across the country literally self-isolated in the (hopefully) virus-free confines of his cab, but having to venture outside periodically for rest stops, food and fuel.

My first reaction was, and not for the first time, to give silent thanks to the truckers, health care professionals, first responders and all the others who are putting their lives on the line to keep the lights on for all the rest of us, including even cranky old intermodal analysts.

But another thought occurred to me as I read about the driver’s lonely journey across 1,079 miles from Richmond, Virginia to Marshalltown, Iowa hauling a load of condenser coils: Why are we asking drivers to take these risks? Wouldn’t it have made more sense all around if this load had moved via intermodal?

Of course, the reality is intermodal wasn’t an economic option for this move, at least not now. It’s exactly the kind of long-haul but hinterland-to-hinterland load that the newly simplified PSR-driven intermodal network can’t support. It won’t move via intermodal because a reasonable service between intermodal terminals that are within striking distance of its origin and destination points does not exist.

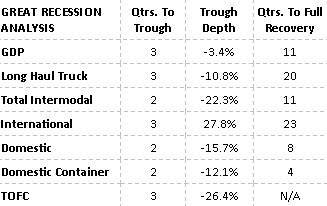

The current situation has some similarities, both in the sudden onset and potentially in the duration of the initial event, to the Great Recession. The table below describes the course of events after 2008 Q3, the last “semi-normal” quarter before the crash. The Great Recession actually had started a year earlier, in 2007 Q4. But 2008 Q3 is a better analogy for what is currently happening. This table provides data on how many quarters it took before things bottomed out, how deep the decline was versus 2008 Q3, and how long it took to regain the ground lost.

Of all the modes, the best Great Recession story was the one told by domestic intermodal and in particular, Domestic Container. Domestic intermodal’s downturn was relatively mild and brief and was mostly on the trailer side. Domestic Container fell for a couple of quarters and then quickly rebounded. 2009 Domestic Container volume actually exceeded that of 2008. Meanwhile, TOFC volume tanked and has never fully recovered the damage to this day.

Of course there are a lot of differences with the current situation. Most importantly, current estimates indicate that the overall slowdown could be significantly more severe in 2020 Q2 than was the case during the Great Recession with some anticipating a drop (remember, annualized) of 30% or more. This would be over four times the worst decrease seen in 2008. But helping to offset the carnage will be the Federal disaster relief CARES Act which will pump trillions of dollars into the economy. Much will depend on the speed with which the money is disbursed and whether it gets into the hands of those who truly need and will spend it. The other big question, unanswerable at the moment, is how long the acute crisis will last.

But while intermodal transport is a derived demand that depends on the state of the economy, the industry is far from helpless. It won’t have much control over the roughly 60% International share of the business. That’s going to be determined by the level of our imports and exports and how they are routed. But the remaining 40% is in play.

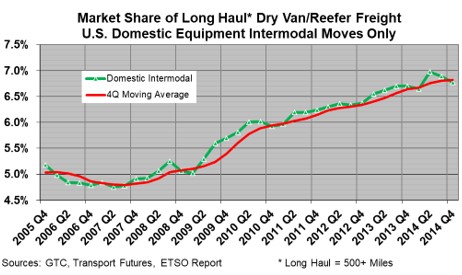

History says it is indeed possible to wring benefits from such a bad situation. In 2008, Domestic intermodal was just entering its golden era of growth as the Great Recession hit. The growth orientation of the railroads and their intermodal partners were a big reason why the sector rebounded so quickly from the downturn. As of the crash in 2008 Q3, Domestic intermodal held a 5.0% share of long-haul truckload moves. Two years later, in 2010 Q2, share had jumped a full point to 6.0%. This was a remarkable achievement because Domestic intermodal had never before reached such levels of share. In subsequent years, although the rate of improvement slowed, market share gains continued. The industry’s performance during the downturn had successfully set the stage for prolonged gains.

The situation is different today. Domestic intermodal has recently lost share. As of the end of last year, domestic intermodal share stood at 6.5% of long-haul truckloads, down 0.6% from the peak in 2018 Q2. The lost volume represents a clear opportunity for share recapture if the industry chooses to do so. An increase of 0.2% share per quarter will add over 3% growth per quarter or almost 10% by year end. If the industry could achieve new record levels of Domestic share during the Great Recession, shouldn’t it at least be able to recapture recently lost share this time around?

During this looming period of economic stress, price will be king. Capacity will be abundant. Service requirements will be relegated to second place. Shippers will be willing to compromise on speed and relax reliability requirements in order to save a buck. This is where intermodal, with its superior cost structure, can come into play. The key is whether the industry, and primarily the railroads, are willing to make the changes needed in order to get back in the game.

Last year, the rail industry’s focus on maintaining and driving down Operating Ratio was a significant factor leading to market share loss. Current railroad management seeks OR’s in the high 50’s but domestic intermodal competes in a world where even the best truckload motor carriers can only support OR’s in the 80’s. For domestic intermodal to achieve the profitability level desired by rail top management it needs to have a highly selective view of the market. Such high margins can only be achieved in quite special situations where all the stars align in favor of intermodal. These typically are markets where high point-to-point volumes can be marshalled with little intermediate handling and minimal highway drayage. IPI fits this model well. But you’re going to write off the Richmond-to-Marshalltown moves with this strategy. These hinterland-to-hinterland hauls represent a large piece of the long-haul freight market and their absence from the rail is a big reason that intermodal share is as low as it is.

At the outset of the PSR revolution, advocates held out the potential for a greatly improved merchandise network with block-swapping that could theoretically support a melded intermodal operation. If one can achieve a truly scheduled carload train that operates on a consistent basis, why couldn’t you put a block of intermodal on the train? Wouldn’t it then be possible to put together a low-cost intermodal option for connecting these secondary points via mixed trains, supported by an advanced block-swapping strategy?

Of course, that’s not how PSR has played out thus far. The plan just described would be complex, and PSR is all about simple. But there is another option to tap at least some of this hinterland traffic. By lowering terminal-to-terminal rates, the railroads can extend the radius of the geographic markets that can be economically served by the existing terminal network. The cost of longer-haul drays can be supported while staying below the competitive pricing of door-to-door direct truckload. Lower prices bring more volume, not only because of deeper penetration in the major markets, but also by making at least a portion of the secondary markets intermodal-accessible.

Prior to the crisis, such a strategy was apparently off the table. The railroads felt that OR had to maintained at all costs because that was what Wall Street was watching. It was (rightly) feared that any deterioration in operating ratio in the quarterly financials would result in quick punishment in the form of lower stock prices. However, since February, railroad stock prices have tanked, sinking over 30% in some instances. How relevant is maintaining the OR in such circumstances? The concern now should be attracting sufficient volume to absorb fixed costs and grow overall profits and return on total investment.

The industry is facing a significant fork in the road. It can double down on the PSR path and cut service and costs, stack up the empty domestic containers in storage, hold pricing and try and ride out the storm. In such instance, the domestic intermodal that emerges at the other end will be a weaker, less relevant presence than it is today.

Alternatively, the industry can lean into the crisis, pivot from focusing on margin to focusing on volume and wring some benefit from this terrible situation by gaining market share. This will put the industry in a better position when we begin to emerge on the other side.