Lawrence Gross, president and founder, Gross Transportation Consulting, and JOC analyst | May 26, 2022 5:27PM EDT

Comparing the recent performance of the US intermodal network with competing truck service and long-term trends indicates there is cause for concern for railroads and intermodal providers.

When analyzing total quarterly intermodal revenue movements as reported by the Intermodal Association of North America (IANA) alongside long-haul truck movements calculated by Noel Perry, principal at consulting firm Transport Futures, the modern intermodal age can be divided into approximately three eras. From 2000 through the beginning of the recovery from the Great Recession, international volume dominated the intermodal picture, with the nascent offshoring boom providing the horsepower. Coming out of the Great Recession, through about the beginning of 2015, the industry experienced the golden era of domestic intermodal, with new corridors and terminals being added to the network on an ongoing basis. Since 2015, the intermodal sector has seen frequent turbulence, with less emphasis on growth amid the onset of the precision scheduled railroading (PSR) operating model.

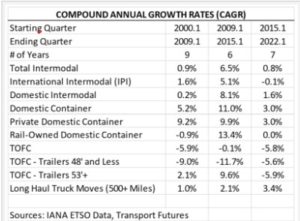

The table below displays the compound annual growth rate for various intermodal sectors and compares them with truck for the three periods:

From 2000 through 2009, the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for intermodal was very close to that of long-haul truck thanks to international intermodal volume — also called inland point intermodal (IPI). Domestic intermodal, on the other hand, scarcely budged. Domestic container volume was growing quickly, but most of the gains were being generated by trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) conversion, which had no effect on the overall domestic volume.

The six years following the Great Recession were a very different story. Intermodal volumes grew far faster than trucking, led by gains in domestic activity. Domestic container volumes grew mightily, while TOFC held steady. The largest gains were recorded by the railroad-owned domestic container fleet.

Intermodal’s sunny skies clouded over starting in 2015. In the past seven years, from the first quarter of 2015 to the first quarter of 2022, overall volumes have grown less than 1 percent per year, far below the robust 3.4 percent annual gains in trucking during the same period. IPI has stagnated, as have rail-owned domestic container moves. Private domestic container activity has grown almost, but not quite, as fast as trucking, but these gains have been offset by losses in TOFC. As a result, overall domestic intermodal activity has trailed that of trucking by a wide margin.

What are the differences between the pre-2015 period and now? One can certainly make the case that the environment for IPI has changed, with a shift in imports from the West Coast to the East Coast and increased transloading dragging on the results. In the latter case, IPI’s loss should have been domestic intermodal’s gain.

But when it comes to domestic intermodal, the overall environment has not changed substantially from the pre-2015 period to now. Rather, it has been intermodal and the growth imperative that has changed.

The good news is that growth is clearly attainable. The intermodal sector grew steadily for six years, and it could do so again.

What is not clear is whether growth can be achieved under the current, somewhat cramped view of how the industry needs to function. Specifically, how much further growth can be achieved when all volume needs to move in massive trains over a simplified network with minimal switching between origin and destination?

The domestic freight world is complex and dispersed. Tapping into the potential will require a rebalancing of power among the railroad operations, finance, and marketing departments. Markets have been exited in the name of simplicity and profitability, and this trend will have to be reversed for growth to resume.

Contact Lawrence Gross at lgross@intermodalindepth.com and follow him on Twitter: @intermodalist.