As the Covid-19 virus spreads rapidly in the United States and the World Health Organization officially declares a pandemic, it appears increasingly likely if not inevitable that the current, record-length economic recovery is nearing an end. Although the economy had a fairly good head of steam coming into the crisis, its heavy reliance on the consumer will make it particularly vulnerable to the pullback in consumer spending that will result from the changes wrought by the Coronavirus. Hence, an acute slowdown in Q1 and a pullback in Q2 appear likely for the first time since 2008. What will this mean for intermodal? A look at how intermodal performed the last time provides some clues, but intermodal is perhaps not as well positioned this time around.

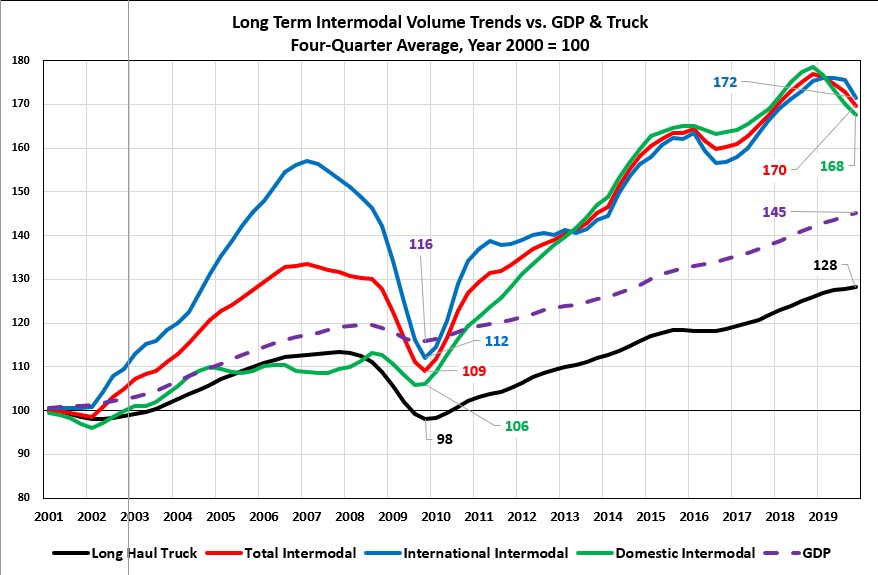

This chart provides a long-term look at how intermodal and its main components have performed long-term versus truck and GDP. Volume is indexed with the average quarterly volume for the year 2000 set as 100. The four-quarter moving average is used for all but the GDP figure to wash out seasonal variations.

First, some general observations. Long-haul (500+ miles) truck volume has underperformed GDP. Share shift to intermodal takes some of the responsibility, but a shift towards shorter hauls and better packaging (more product per trailer) account for most of the difference. Intermodal has generally out-performed both GDP and long-haul truck. Both truck and intermodal are extremely sensitive to even small changes in GDP.

Looking at 2008, truck loadings provided some advance warning of the slowdown. Although the market crash occurred in October 2018, long-haul truck loadings actually began to decline in 2008 Q1 and continued throughout the year. The plunge accelerated in 2019 Q1 and things bottomed out in 2019 Q2. Intermodal also showed declines in advance of the meltdown. In the case of International intermodal (IPI), the drop actually started in early 2007 as a function of importers shifting from Southern California to “four-corner” import strategies. The rate of decline accelerated in 2009 with the trough occurring in 2019 Q2. But the snap-back was equally strong. The impact on the Domestic intermodal sector was much less severe. In fact, domestic container volume never actually fell below prior year. TOFC absorbed the brunt of the damage.

The 2008 recession ushered in what might be regarded as the “golden era” of domestic intermodal. Growth continued over the next eight years as railroads added routes, terminals and converted from TOFC to domestic container. This era came to a close in 2016 and since then, performance has been quite a bit more choppy and driven by non-economic factors, the ELD mandate most importantly.

Looking at the run-up to today, there are some important differences from 2008. Although growth in truck loadings has slowed, truck volume has not been declining. In contrast, intermodal volume has been dropping across the board. Far from increasing services, railroads have been trimming their intermodal offerings and simplifying their networks in pursuit of PSR-related goals. Meanwhile, the railroads have tried to hold intermodal rates up in the face of softer market conditions in the interest of continuing to drive down their operating ratios in the manner prized by Wall Street.

Now, in just a few weeks, the game has changed. Low operating ratios don’t seem to count with investors right now, as volume concerns have come to the fore. U.S. Class I stock prices have plummeted by 25% or more. The silver lining is perhaps that freed of the quarterly tyranny of the need to drive operating ratio down, rail managers may utilize more pricing flexibility to entice volume back to intermodal from the highway.

The PSR mantra was that by slimming down the intermodal network, improved service would drive market share gains on the main lanes. This was a questionable assumption because it wasn’t clear how large the intermodal share already was between those major city-pairs and how much traffic was left to convert. There was also an underlying expectation that the truck market would return to “normal” and that pricing pressures would ease. This expectation was always somewhat unrealistic but now is completely out the window.

From an intermodal perspective, the looming downturn appears to have four chapters. We’re currently in Chapter One, during which volume is being driven down by the problems in China. Chapter Two will see knock-on effects of the China situation, including component shortages and production snafus in North America plus supply chain disruptions and imbalances. The China situation will be short-lived. In fact, things may already be beginning to normalize over there. But by the time that improvement works its way over to North America, we’ll already be in the throes of Chapter Three, which will be a decline in demand as the economy slows. At some point thereafter, we’ll reach Chapter Four – recovery. Whether the downturn is short and mild or long and deep depends less on economics and more on biological factors that are beyond the capability of any economic analyst to project.