As these words are written, the Coronavirus crisis centered in Wuhan, China appears to be cascading rapidly. The population of Wuhan is trapped in a virtual prison with infected individuals (and those suspected of being infected) being crammed together in massive but makeshift and improvised health-care facilities. The quality of care in such places is at best uncertain, and the risk to those as yet unaffected is high. Even if the spread of the virus is ultimately successfully confined to China (a very big if, to be sure), the damage to global supply chains will already be severe.

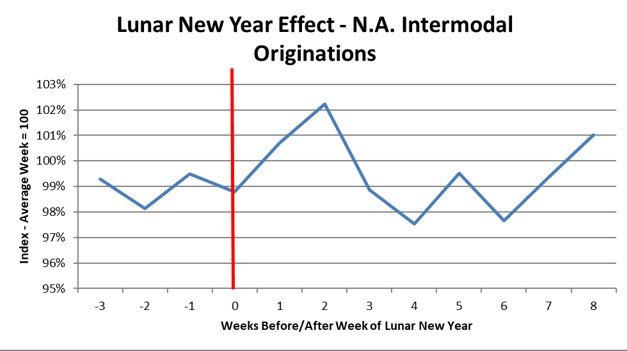

The impact, though imminent, is yet to be felt here in North America. This year, the Lunar New Year holiday fell on January 25. The chart below looks at weekly intermodal activity as reported by the AAR in the weeks before and after the Lunar New Year. Typically, North American intermodal originations peak in the second week after Lunar New Year, as the pre-holiday production surge that took place immediately prior to the LNY shutdown hits North American shores. Thus, the pre-LNY peak is taking place right now, the first week of February. If things track as normal, volume will decline over the 2nd and 3rd week of February, but that won’t yet be due to the Coronavirus. That will simply be the normal pattern as the effects of the Lunar New Year shutdown reach our shores.

This year the Lunar New Year shutdown has been extended by a week due to the virus. That implies a weaker performance in week 5, when things normally start to recover. In other words, the first real impacts will be felt in North America at the end of this month on the rails, and a bit earlier in the ports. After that, how bad could it get?

Well, pretty bad. According to IHS Markit PIERS data, 9.9 million TEUs, fully 40% of U.S. containerized import TEUs, originated from mainland China in the year 2019. For the major ports, China import share ranged from a high of 59% of all TEUs coming into Los Angeles/Long Beach, down to shares in the high 20% range for Northeast U.S. ports. Just looking at these straightforward share figures is alarming enough, but in truth they understate the problem. Many of those TEUs are not carrying finished goods, but rather materials and intermediate components to be used in further production to be transformed into finished products. Any extended disruption to the supply chains involved could result in lost production, in effect creating a multiplier effect to the virus’s direct supply chain impact. Another potential downside would be if the virus spreads to China’s immediate neighbors. South Korea originated 1.9 million TEUs to the U.S. in 2019. Viet Nam was responsible for 1.1 million and Taiwan another 1.0 million. Collectively, these three nations generated about 40% of the volume that China did.

The world economy is already in a somewhat fragile state. While it is early days yet, it appears that while the mortality rate of the Coronavirus is lower than previous such outbreaks such as SARS, the virus appears to be much easier to transmit. While the survival rate appears to be excellent with proper medical care, will such care be available on a global basis if huge numbers of individuals are infected?

While time is short, supply chain participants should be working hard to put into place contingency plans, not only for what appears to be inevitable near-term disruption of their China-based supply chains, but also for potential knock-on effects that could extend well beyond the Chinese economic sphere.

In the long run, the tectonic forces that had already been set into motion by the China tariffs will be accelerated. For the second time in less than two years, the dangers of excessive geographic concentration of supply chain sourcing have been demonstrated. The diversification of global sourcing away from excessive dependence on China will be accelerated.

No doubt there will be near-term impacts on China’s economy stemming directly from the virus and its effects. Recovery of this export-led economy will then be impaired by supply chain diversification away from China sourcing. The geo-political risk is considerable. The dominance of China’s one-party system has rested on an unwritten bargain with the nation’s population. In essence: “let us (the Party) run the country and we’ll deliver a growing economy and a rising standard of living.” The standing of the Communist Party has already been shaken by its initial missteps in handling the crisis. We could easily see further disruption in this key component in the international economy as a result of this crisis, with potential significant global economic effects.